It’s a simple premise, much like Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works, loonshots are crazy ideas that are often dismissed as unwise, but may not be so crazy after all. As the title says, these are ideas that can win wars, cure diseases and transform industries. It’s a theory that physicist, biotech entrepreneur, and former CEO Safi Bahcall, supports using former US science policy adviser Vannevar Bush’s theories, the physics concepts of phase transitions and illustrates parallels to innovation management theories.

The Loonshot Thesis

Here’s how Bahcall sums up the Loonshots thesis in the book:

- The most important breakthroughs come from loonshots, widely dismissed ideas whose champions are often written off as crazy.

- Large groups of people are needed to translate those breakthroughs into technologies that win wars, products that save lives, or strategies that change industries.

- Applying the science of phase transitions to the behavior of teams, companies, or any group with a mission provides practical rules for nurturing loonshots faster and better.

It’s a thesis he’s turned into a Wallstreet Journal best-selling book, Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries. Bill Gates recommends it, and Tim Ferris (you can listen to his interview with Bahcall here). Loonshots has been selected by Dan Pink as one of the “two most groundbreaking new nonfiction reads of the season,” and is heralded as “Best Business Book of 2019” by strategy + business. If you feel big names and big claims deem a book worthy of your time, then that is one reason this book is worthy of your time.

Ill-Shapen Innovations

Bahcall quotes Sir Francis Bacon, “As the births of living creatures are at first ill-shapen, so are all Innovations, which are the births of time.”

Leaders often dismiss the very “out of the box” ideas they claim to want, usually because the thought has yet to be fully developed. Bahcall’s point is that innovative, early-stage ideas rarely show up perfectly packaged, handed to you with a bow, and a note that reads, “this is a valuable idea, please pursue me,” which is why they’re so often killed before they even start.

Inspired by a conversation over a drink of whiskey with Sir James Black, winner of the 1988 Nobel Prize, the first law of the Five Laws of Loonshots, is based on just that theory, that revolutionary ideas may suffer through hard times, “The most important breakthroughs aren’t showered with tools and money and offers of help. They pass through long dark tunnels of skepticism and uncertainty, crushed or neglected; their champions often dismissed as crazy.”

Engaging us through his storytelling, Bahcall weaves history lessons into compelling arguments for backing your loonshots. One of those such stories is based on Nokia. In a parallel universe, Nokia could have been what Apple is today if it weren’t for a missed shot.

In the early 2000s, half of the smartphones were sold through Nokia, whose culture promoted a “safe place,” where it was ok to make mistakes and have fun, encouraging creativity and innovation. It was this culture that led their engineers to propose a new cellphone model that would end up looking an awful lot like the yet to be seen iPhone … if only they had said yes.

Three years later, the iPhone launched to global acclaim.

Water freezes, Systems Snap: The Tug of War

Using phase transitions to illustrate his point, Bahcall compares the snapping of a system due to competing incentives to water freezing. “As teams and companies grow larger, the stakes in outcome decrease while the perks of rank increase. When the two cross, the system snaps. Incentives begin encouraging behavior no one wants. Those same groups—with the same people—begin rejecting loonshots.”

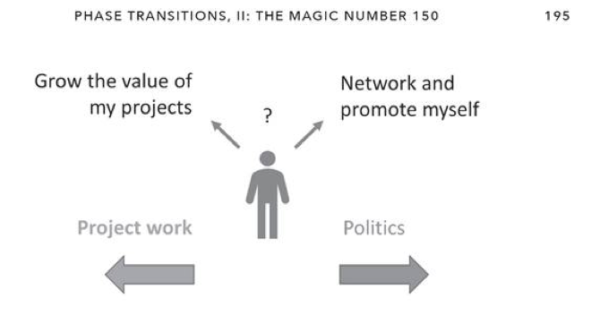

This illustration from Loonshots is highly thought provoking, illustrating the phase transition in organizations (think molecules of water transitioning into ice). When a company’s size increases, politics increase. With increased politics comes decreased innovation, or less risk taking. I’ve seen this transition many times throughout my career and often with many of our large multi-national clients.

Bahcall further explains that rather than a shift in culture, small structural changes can be made to create a nurturing environment for loonshots and transformation of a rigid team. Rather than creating incentives that drive employees to network and promote their own agendas, align incentives, so employees focus on growing the value of their projects. This was reassuring because Bedrock-Service’s operations are aligned to this delivery model.

There is no denying that banking on loonshots can be high-risk. However, radical, breakthrough innovations rarely come easily. Knowing what to pay attention to, when to cease, and when to push on, is perhaps another lesson we can learn.

“When asked what it takes to win a Nobel Prize, Crick said, ‘Oh it’s very simple. My secret had been I know what to ignore.’” ― Safi Bahcall

There are many gems to be mined from this book regarding leadership, organizational management and project management. Although you may not be building the next iPhone, I highly recommend Loonshots for all project professionals working in any size organization.